Hearken to this text

Produced by ElevenLabs and Information Over Audio (NOA) utilizing AI narration.

When Kathleen Walker-Meikle, a historian on the College of Basel, in Switzerland, ponders the Center Ages, her thoughts tends to float to not non secular conquest or Viking raids, however to squirrels. Tawny-backed, white-bellied, tufted-eared pink squirrels, to be precise. For tons of of years, society’s elites stitched red-squirrel pelts into luxurious floor-length capes and made the animals pets, cradling them of their lap and commissioning gold collars festooned with pearls. Human lives had been so intertwined with these of pink squirrels that considered one of historical past’s most cursed ailments seemingly handed repeatedly between our species and theirs, based on new analysis that Walker-Meikle contributed to.

Uncomfortable questions on medieval squirrels first got here up a couple of decade in the past, after one other group of researchers stumbled upon three populations of pink squirrels—one in Scotland, two on completely different English islands—with odd-looking options: swollen lips, warty noses, pores and skin on their ears that had grown thick and crusty. A seek for microbial DNA in a few of these squirrels’ tissues revealed that they’d leprosy. “What’s it doing in pink squirrels?” John Spencer, a microbiologist at Colorado State College, recalled considering on the time. Scientists had lengthy thought that leprosy affected solely people, till the Seventies, after they started to search out the bacterium that causes it in armadillos too, Daniel Romero-Alvarez, an infectious-disease ecologist and epidemiologist at Universidad Internacional SEK, in Ecuador, advised me. However that was within the Americas; in Europe, dogma held that leprosy had primarily vanished by concerning the sixteenth century. Essentially the most believable rationalization for the pathogen’s presence in fashionable squirrels, Spencer advised me, was that strains of it had been percolating within the rodents unnoticed for tons of of years.

Bacterial genomes extracted from a number of of the contaminated British squirrels urged that this was the case: These sequences bore a powerful resemblance to others beforehand pulled out of medieval human stays. The following step was proving that medieval squirrels carried the bacterium too, Verena Schünemann, a paleogeneticist on the College of Zurich, in Switzerland, and one of many new research’s authors, advised me. If these microbes had been additionally genetically much like ones present in medieval individuals, they’d present that leprosy had in all probability usually jumped between rodents and people.

Schünemann teamed up with Sarah Inskip, an archaeologist on the College of Leicester, within the U.Ok., and got down to discover an archaeological web site in Britain with each human and squirrel stays. They zeroed in on the medieval metropolis of Winchester, as soon as well-known for its fur-obsessed market patrons, in addition to a big leprosarium. After analyzing dozens of samples from round Winchester, the workforce was in a position to extract simply 4 leprosy genomes—three from people, one from the tiny foot bone of a squirrel. However these turned out to be sufficient. All 4 samples dated to concerning the Excessive Center Ages—the oldest detection to this point of leprosy in a nonhuman animal, Inskip advised me. The genomes additionally all budded from the identical department of the leprosy household tree, sharing sufficient genetic similarities that they strongly indicated that medieval people and squirrels had been swapping the disease-causing bugs, Schünemann advised me.

Nonetheless, Schünemann wasn’t certain precisely how that will have occurred, on condition that transmitting a leprosy an infection usually requires extended and shut contact. So, hoping to fill within the blanks, she reached out to Walker-Meikle, who has extensively studied medieval pets.

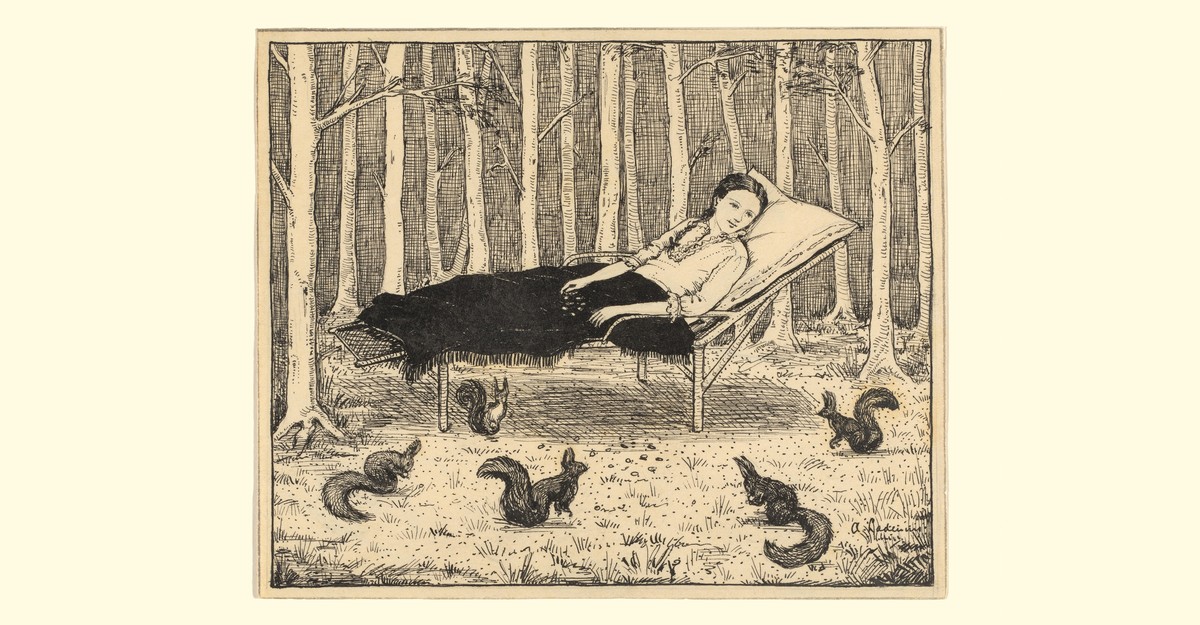

Walker-Meikle already had the precise sort of proof that Schünemann and her colleagues had been on the lookout for: medieval paintings depicting individuals cradling the animals, paperwork describing girls taking them out for walks, monetary accounts detailing purchases of flashy, rodent-size equipment and enclosures of the kind individuals at present may purchase for pet canine, Walker-Meikle advised me. Squirrels had been so common on the time that she discovered written references to the woes of a Thirteenth-century archbishop who, regardless of years of pleading, couldn’t get the nuns in his district to cease doting on the creatures. They had been primarily akin, she mentioned, to tiny lapdogs. Fur processing, too, would have offered ample alternative for unfold. Within the Excessive and Late Center Ages, squirrel fur was the most well-liked fur used to trim and line clothes, and garments made with it had been thought-about as excessive trend as a Prada bag now, Schünemann advised me. In a single 12 months within the 14th century, the English royal family bought practically 80,000 squirrel-belly skins. Contact between squirrels and people was so intimate that, all through a lot of the Center Ages, leprosy seemingly ping-ponged backwards and forwards between the 2 species, Inskip advised me.

However the workforce’s work doesn’t say something concerning the origins of leprosy, which entered people at the very least hundreds of years in the past. It can also’t show whether or not leprosy infiltrated people or pink squirrels first. It does additional dispel the notion that leprosy is an issue just for people, Romero-Alvarez advised me. Armadillos might have picked up leprosy from people comparatively lately, after Europeans imported the pathogen to South America. The scaly mammals are actually “giving it again to people,” Spencer advised me, particularly, it appears, in elements of South America and the southern United States, the place some communities hunt and eat the animals or maintain them as pets.

Human-to-human transmission nonetheless accounts for almost all of leprosy unfold, which stays unusual total. However Romero-Alvarez identified that the mere existence of the bacterium in one other species, from which we and different creatures can catch it, makes the illness that rather more troublesome to regulate. “Everyone believes that leprosy is gone,” Claudio Guedes Salgado, an immunologist at Pará Federal College, in Brazil, advised me. “However we now have extra leprosy than the world believes.” The boundaries between species are porous. And as soon as a pathogen crosses over, that bounce is inconceivable to completely undo.